African Americans During World War II

For African Americans, the war era began in a fashion distressingly similar to the decades that preceded it. The experience was particularly frustrating for black men and women who sought roles in defense work, other civilian support functions, or service in the military itself. As in World War I, initial progress in racial matters resulted principally from personnel shortages, but it also was the product of leaders in the black community fighting for racial justice. As early as June of 1941, well before the start of combat, President Roosevelt issued an executive order outlawing discrimination in the hiring of defense workers. Jim Crow, however, was a stubborn foe.

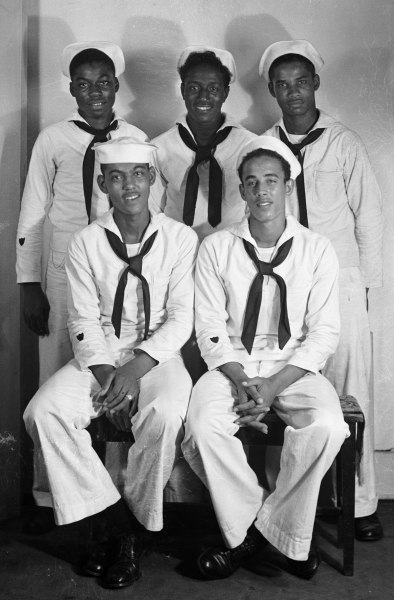

Although 2.5 million black men registered for the draft during 1941, only 4,000 were in uniform when the war began, with only 12 ranking as officers. Some draft boards in southern states refused to consider any black candidates for immediate active duty. Those who did secure access to military service were typically assigned to kitchen, laundry, and other maintenance duties. The blood of willing black contributors was segregated from blood by whites donated to the American Red Cross. Well into the conflict, then, conditions for the nation’s largest minority group improved only marginally from their prewar level.

In and out of uniform, however, gains recorded by African-American men and women accelerated steadily as the war approached its midpoint. Some of the impetus came from the top as President Roosevelt decreed that the numbers of blacks in the military would match their ten percent share of the national population. Women who served in the Women’s Army Corps, in fact, were often described as “10-percenters” following Roosevelt’s order.

The presidential target went unmet by the nation’s service branches, where, member totals of eight to nine percent were usually the norm. Having resisted the objective from the start, the Navy’s participation never exceeded five percent. Until late in the war, America’s entire military force was segregated by race. That practice was impractical on the home front, however, as black males and females worked beside their white colleagues. But discrimination did exist across the nation’s production capacity, most notably in the whites-first order of hiring and promotions and the nature of work involved. African-American women frequently were assigned to assemble the most sensitive explosive devices or to a facility’s more toxic work environments and the first jobs available to men involved maintenance duties. As the demand for help grew, and black workers’ commitment and reliability were recognized, other positions became available. Women became fully credentialed “Rosies,” and men assumed positions in every facet of wartime production. Their experience serving in World War II provided black citizens a path to employment opportunities somewhat equal to those enjoyed by their white co-workers. They helped form the foundation upon which later generations of advocates of racial equality would stand to make their case.

Although still limited to behind-the-lines support roles, contributions by black servicemen in combat areas also rose as their numbers increased. A breakthrough occurred in 1943 with the arrival of the 332nd Fighter Group of the 15th Air Force – the storied Tuskegee Airmen. Beginning with support missions over Anzio and continuing as fighter escorts during bombing runs to southern Italy, the group flew more than 15,000 sorties in the two years beginning in May of 1943. Many of those missions were in response to bomber commands requesting their presence. The Western Pennsylvania Tuskegee Airmen Memorial in Sewickley recognizes 101 members of the group. Although that total included volunteers from well beyond metropolitan Pittsburgh, no region in America matched its count of serving Airmen. After the 1944 invasion of German occupied France, the presence of black troops was much more prominent. Some 1,500 landed in Normandy on D-Day. An all-black tank battalion fought with Patton across France, and was credited with the capture of 30 towns along the way. By 1945, more than one million African Americans were serving in almost every combat capacity, albeit separately from their white comrades. The division prompted a memorable comment from historian Stephen Ambrose: “The world’s greatest democracy defeated the world’s greatest racist with a segregated army.” Calling for the integration of that force, Pittsburgh reporter Frank Bolden wrote, “It’s not where we came from, but where we’re going that counts. Our ancestors came on different boats, but we’re all in the same boat now.”